8 Projected effects of migration pressures on land use change at NUTSx

The paper from now on looks at the analysis of the material presented in the review and attempts to interpret it into potential patterns of land use change. Firstly the findings from the review are converted into major patterns of migration flows and secondly these flows are converted into a model of projected land use change resolved to NUTSx. The calculation of this and the shift from NUTS 2 to NUTSx was carried out by examining the NUTSx maps and identifying which areas were primarily urban, primarily rural or a mix of the two and whether they were locations of out-, in- or no-net migration. From this the likely shift in land use was assessed. The literature also helped to identify specific trends in each country which could be ascribed to the relevant land use types (Kröhnert et al., 2008). This approach is recognised as being somewhat crude and is likely to be significantly revised if and when better and more comprehensive data becomes available. However, it is a first initial step at trying to relate data from a range of sources which do not explicitly discuss land use into implications for land use change.The analysis process identified that there are several types of land use change currently taking place, sometimes with a number of sub-types occurring within each NUTSx region. These land use changes taken from the evidence of studies from various locations were then extrapolated into other similar areas. This basic interpretation would enable a certain degree of modelling within a region to be developed if so wished, as part of a future research project. Three case studies illustrate three aspects of land use change in response to migration in order to demonstrate that these responses actually occur.

The following Table 5 describes the land use change typology adopted here and Figure 8* presents the spatial pattern. Because Europe is still largely rural despite the scale of urbanisation the map seems to show more rural types than urban types. However, many rural NUTSx regions contain towns and other urban areas while the urban areas may appear as the core territory surrounded by a peri-urban ring. This depends on the way the NUTSx boundaries have been drawn so the degree of detail for urban and peri-urban regions varies from country to country. This is a drawback in the model, especially when peri-urban areas are a focus of land use change studies as in the PLUREL project but it is inevitable when the scale of resolution is NUTSx.

|

Cat. |

Type |

Migration character |

Land use change character |

Locations where this change takes place |

|

1 |

Abandoned rural |

Flow of young people to cities, flow of working age people cities or abroad, older residents left behind |

Land abandonment: fields lie uncultivated, empty farms, forest colonising abandoned land, landscape becoming progressively “wilder”. |

Eastern Europe (Baltics away from to main cities), parts of Poland, Bulgaria and Romania, Portugal and Spain, parts of Swiss, Austrian, Italian and Greek mountains. |

|

2 |

Extensified rural |

Flow of young people of young people to cities, general depopulation out of the region. |

Extensification of agriculture and forestry: more land farmed by fewer people, extensive modes of farming and industrial forestry. May be some tourism development in places. |

Eastern Finland, Eastern Germany, parts of Romania, Italy, central Sweden, Hungary, eastern France, Iceland. |

|

3 |

Stable rural |

Slight increase in population but low rates of migration, mostly to urban centres within the area. |

Traditional farming continues or there is extensification in remoter places and tourism development including holiday houses. |

Western and northern Norway, northern Finland, rural Ireland. |

|

4 |

Idyllic rural |

Foreign migration into rural areas by well-off people from elsewhere in Europe or migration to remoter areas within countries. Retirement migration. |

Rural houses and villages are regenerated and revitalised by foreign incomers. Traditional rural landscape is maintained or slightly extensified. Tourism development also uses old settlement infrastructure. |

Western and central France, Central and northern Italy, parts of Portugal and Spain, small trend in Greece, Romania and Bulgaria, northern Scotland and parts of England and Wales. |

|

5 |

Intensive rural |

Labour migration into productive agricultural areas |

Areas where agricultural production and horticulture is economic but relies on low wages. Landscape covered by polytunnels and other modern technology of agriculture. |

Eastern England, Netherlands, southern Spain, Greece |

|

6 |

Grey rural |

International retirement migration from northern to southern Europe |

Ex-urban suburban developments along coastal areas, in association with golf courses and other amenities. |

Southern Spain, southern France and Brittany, the Algarve in Portugal, Greek islands. |

|

7 |

Gentrified rural |

Not strictly migration but movement of better-off people from the city to rural edge or hinterland |

Villages close to large urban centres expand, new residential developments in rural areas within commuting distance of the city. Urbanisation of rural areas (more roads, street lights) and local people priced out of the housing market. |

UK, Ireland, southern Germany, southern Scandinavia, France, national or regional capital cities in most countries or economically developing cities in Eastern Europe. |

|

8 |

Dynamic urban |

National migration from rural to city, EU labour and non-EU immigration, intensive in scale and multi-ethnic in composition in many places. |

Pressure on urban areas leading to densification, reducing quality of some neighbourhood environments as well as urban sprawl. Ethnic composition of some urban districts changes, local population is displaced to the urban fringe. |

Cities in UK, France, central Germany, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavia and other regionally dynamic areas |

|

9 |

Stagnant urban |

Moderate population change from inward and outward migration, net effect being slight reduction in population. Some non-EU immigration substitutes for the loss of national population. |

Some decay of urban infrastructure, reduction in development pressures, increase in brownfield land. |

Central Germany, parts of Eastern Europe, ex-industrial cities across Europe |

|

10 |

Shrinking urban |

Net out-migration from failing cities to other more economically active regions or countries. May be in-migration at a rate that does not balance out-migration |

Reduction in development pressure, vacant housing in less-desirable areas, increase in brownfield sites. |

Eastern Germany, Baltics, regional cities in Eastern Europe. |

The following examples illustrate actual land use changes through different types of migration for three countries in Europe.

8.1 Land abandonment in Latvia as a result of out-migration

Following the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, the rural areas became sources of large-scale out-migration, firstly to towns and cities and, more recently, abroad. The situation in many countries can be exemplified by the case of Latvia, which was part of the Soviet Union and since 2004 is part of the EU. During the Soviet era the countryside was extensively changed through the process of collectivisation, where private land was abolished, the fields were enlarged and often drained for large-scale machinery-based cultivation and the population were moved into blocks of flats in the village centres. People were more-or-less forced to live and work there. Once the system collapsed and Latvia became independent many social and economic forces which had been suppressed were released. The land was restored to the original owners or their descendents and the collective farm system was broken up, leaving a legacy of abandoned buildings and ill-maintained drainage systems. The social and economic hardships which developed from that time were the initial conditions for migration, firstly to the cities and latterly, with the accession of Latvia to the EU in 2004, migration abroad (Bell, 2009a*).

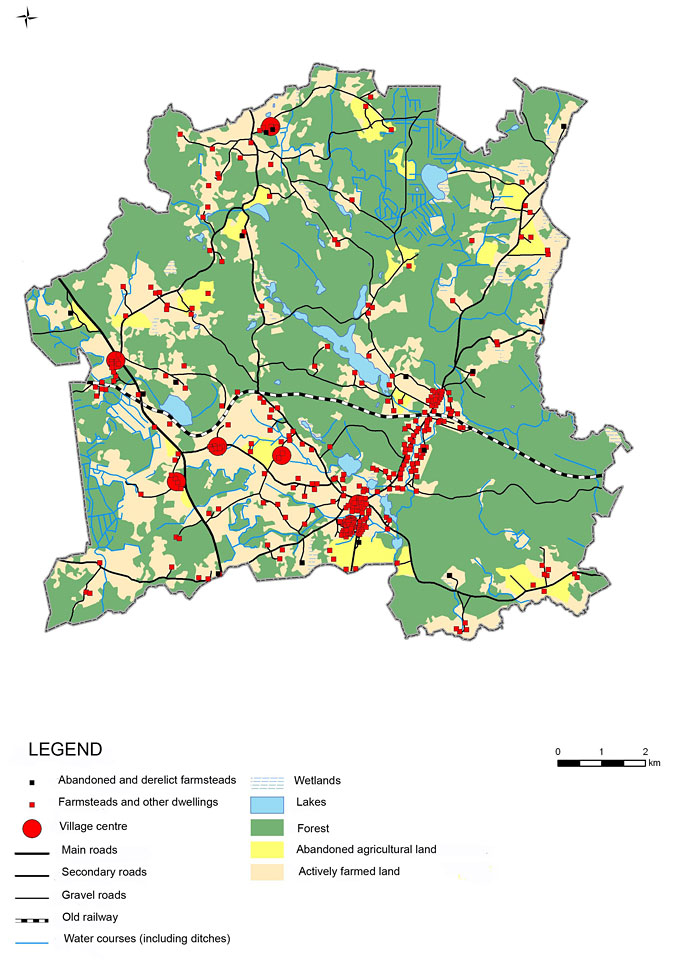

The drivers of migration are as follows: the main push factor is the absence of jobs and low quality of life in rural areas as well as the dismantling of the collective farms system in the early 1990s (Bell et al., 2009a; Bell, 2009a; Bell et al., 2008). The pull factors include the opportunities for education and better paid jobs in urban areas, especially the capital, Riga and, since 2004, the prospects of employment abroad, especially in the UK and Ireland. The results of the depopulation include a marginalised and impoverished older population suffering social and economic isolation in more remote rural areas as well as large-scale land abandonment in part due to lower levels of land management by these older people as well as absentee owners who received their land at the restitution but who do not live there, resulting in natural re-afforestation of cultural landscapes and widespread presence of ruined buildings from Soviet and pre-Soviet times (Bell et al., 2009b; Bell, 2009b). Figure 9* shows a map of one rural municipality demonstrating the extent of abandoned land. Figures 10*a–c show abandoned land turning to forest, a Soviet-era ruin from a collective farm, and a collapsed old farmhouse.

8.2 Suburbanisation of the rural coastal landscape in Spain as a result of international retirement migration

In southern Spain an influx of retired people from Northern Europe to live there year round has occurred over the last 20 years. Amenity related migration, the category described here is sought by older people who are usually in good health and who have the social and financial resources to support their decision to move. This group of retirees target ‘Sunbelt’ areas, such as the Alicante region of Spain. It includes ‘multiple movers’ defined in the literature as including seasonal migrants; ‘second home owners’ or ‘third-age long-stay tourists’ (Williams et al., 1997). Britons are attracted to Spain by the combination of a high quality of life and a warm and sunny climate as well as low housing costs, although this has changed to some degree with housing price inflation and, very recently, with a change in the exchange rate devaluing the pound against the Euro.

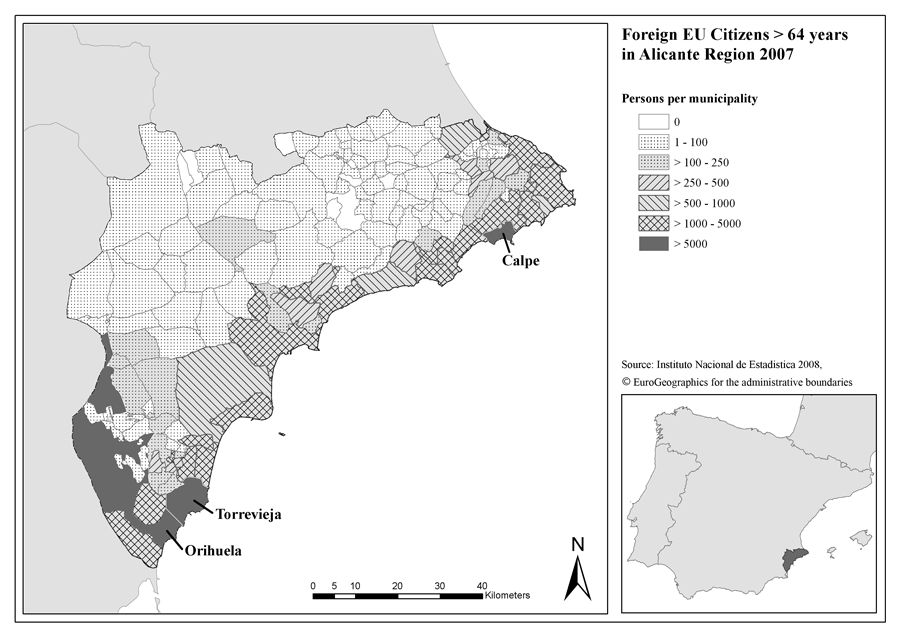

The characteristics of retirees are that 1) they are highly culturally embedded within their British and Northern European perceptions of landscape and urban tradition; (2) they demand a hedonistic lifestyle focusing on natural amenity; and (3) leisure as well as age-specific requirements are central features of IRM, which can be related to demands on and expectations of the appearance of the urban landscape. The density of settlement is greatest within a 10 km zone from the coast and it produces a mixed landscape where the clear distinction between dense urban development and broad rural areas has become blurred by numbers of suburban and exurban suburb-like developments interspersed with irrigated golf courses. This results in impacts on the environment such as water demand for human consumption and irrigation, loss of soil and increased salinisation, fragmentation of habitats, creation of gated communities and other leisure landscapes with restricted access and demand for other features such as shopping centres and infrastructure (Zasada et al., 2010*). Figure 11* shows the distribution of foreign EU citizens over 64 years of age in the Alicante region, with strong coastal density pattern very evident. Figure 12* shows some of the typical landscape elements created as a result of international retirement migration.

8.3 Urban growth in Lisbon as a result of immigration

Over the past forty years Portugal has seen significant immigration from the African ex-colonies, Brazil and more recently Eastern Europe. The Cape Verdeans were the first group to arrive in the late 1960s, followed by the Brazilians in the 1990s, and more recently the Ukrainians in the beginning of 2000. According to the latest statistics these three nationalities constituted the three main communities (SEF, 2010). The migrants mainly come to work in low-status and low-skilled service jobs, or the so called 3D jobs (dirty, dangerous and difficult) (Fonseca et al., 2005; Marques and Góis, 2007) and many remain quite poor. The push factors are unemployment and poverty at home while the pull factors are availability of jobs, better prospects for the future, family reunion, social networks and historical links. In 2001, more than half of the immigrant population was living in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Fonseca, 2003) and due to social and family networks new arrivals tend therefore to gravitate towards locations where their compatriots are to be found, which creates areas within the city where these ethnic groups mainly settle. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Lisbon Metropolitan area started its suburbanisation process with the establishment of unofficial housing in the outskirts of Lisbon in order to accommodate not only the influx of inland migrants from rural areas, but also international migrants from ex-African colonies who built their houses in shanty towns on public land (Castela, 2007). These areas grew outside all the planning regulations (alignments, density, heights, etc.) and without infrastructure, leading to poor environments and poor housing condition (Malheiros and Vala, 2004*).

Cova da Moura neighourhood is one example of this unplanned and illegal genesis (Figures 13*a and 13*b). Two thirds of the resident population in this area have a foreign background (Mendes, 2008*), mainly immigrants from Cape Verde and their descendents, who have, over time, settled in and developed their own unofficial quarters. The southern part of this neighbourhood characterised by densely built informal houses in very poor structural conditions, narrow streets, lack of green spaces, little infrastructure and few amenities (Horta, 2008*; Mendes, 2008), represents, to a certain degree, a rupture in the urban fabric, being characteristically different from its surroundings. Apart from its morphological and physical problems, the neighbourhood is also known for its social problems. The majority of the working population has a low income and low skill jobs: men tend to work in the construction sector, while women are employed in cleaning and domestic jobs (Horta, 2008*). Over recent years the neighbourhood has also been characterised by the media as an unsafe and criminal place, creating the image of a “black ghetto” with an unemployed and troublesome young population (Horta, 2008).

Other areas of the metropolitan area have not developed ad hoc like the district described above but have been filled with poor quality public social housing. These neighbourhoods are often segregated spaces, packed with a low income population and vulnerable groups. The monotony of construction, the similarity of the buildings, colour schemes, facades; the inadequacy of open spaces, the low quality of the social environment, the lack of facilities and amenities (Augusto, 2000) lead to a feeling of exclusion (Figure 13*c).

Although legalisation and urban rehabilitation programmes started to take place during the 1990s in order to clean the slums, revitalise and improve the living and social conditions of some problematic neighbourhoods (Malheiros and Vala, 2004), the signs in the landscape of this unplanned suburbanisation and migratory movements are still visible.