3 Historical patterns and processes of migration

Europe has been characterised by large scale migration events and processes throughout history. These complex migratory movements occurred not only between European countries but also between Europe and the rest of the World (ESPON, 2005*, project 1.1.4). For the purposes of the present study the main influences are rooted in the 19th century onwards. This was the period of the development of the largest colonial empires, which has set the foundations for much of the migration in the 20th and 21st centuries. The 19th century was characterised by the siginificant emigrant flux from many countries of Europe to the United States, Canada and Australia as well as, to a lesser extent, Brazil, Argentina, New Zealand and South Africa. However this tendency changed, and during the second half of the 20th century, Europe became a hosting region, largely as a legacy of the by then dismantled colonial empires and the aftermath of the Second World War. An anomaly to this trend was the flow of refugees as a result of the Balkan wars that took place in the 1990s, especially that in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the reverse flows since 1995 as people returned home (Kröhnert et al., 2008*).

3.1 Phases of migration

The period from 1950 to 1975 was characterised by important intra-European migratory movements between the poor peripheral countries and the rich central countries (France, Germany, and UK) due to the economic push and pull factors and the needs of the labour market. The main direction of flow was from Southern (Mediterranean) to North-Western European countries, especially from Portugal, Turkey, Cyprus and southern Italy but also movements from Ireland to the UK and Finland to Sweden. There were weak movements between Eastern and Western countries mainly because of the barrier formed by the Iron Curtain (ESPON, 2005*, project 1.1.4).

During the 1960s and 1970s the extra-European flows started to exceed the migrations from Southern to Northern Europe. This can be explained using the push-pull model where poor people in former colonial countries such as India, Pakistan, sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean were encouraged to migrate to former imperial powers such as the UK, France, Portugal and the Netherlands in order to fill the labour market for un- or low-skilled workers. These migrants settled in places where certain industries could be found, such as cotton mills and the garment industry for people from the Indian sub-continent in the UK. These locations were later to form important magnets exerting a strong pull for later waves of immigrants from these countries.

From 1975 to 1990 the extra-European flows into Europe decreased. In part this was probably because immigration became more difficult or illegal, and the official numbers decreased while unofficial, illegal immigration increased. During this period the expansion of the EU and the money flowing into the poorer economies started to allow them to develop and to reduce the influence of the push factors of poverty and unemployment, though this process was not to take full effect until the later 1990s.

During the 1990s there was an increase in immigration. Although legislation became more restrictive, extra-European immigration increased as existing immigrants brought over their family dependents to live with them. In terms of intra-European movements, the economic imbalances between areas significantly decreased and living conditions became more uniform among the EU countries. This started to have an effect of increasing the demand for labour in the newly growing economies such as Ireland which started to become a net in-migration country instead of a net out-migration source.

The beginning of the 1990s saw the collapse of the so-called Eastern bloc and the USSR which initially became translated into large-scale flows from Eastern to Western European countries as borders opened. However, this tendency decreased after 1995 as controls came into force in many countries. During the 1990s metropolitan areas were the most favoured spaces for immigrants. This has been a feature of many groups, partly because the urban areas saw the most demand for jobs and partly because immigrants saw a move to another country and an urban lifestyle away from a poor rural village as a social and economic improvement.

According to (Boswell, 2005*), after 1973 – 74, Western Europe followed the same tendency as the rest of the world. As a result of the oil crisis Western Europe as a whole decreased its rate of migrant recruitment, but immigration flows continued in the form of family unification, refugee flows and some labour migration (Castles, 2000*). Subsequently, in the 1980s and 1990s migration levels increased once more as economic growth resumed, reaching particularly high levels (Boswell, 2005*; Castles, 2000). The western (Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, UK) and Nordic European countries are examples of this trend. In 2001 the average net rate of immigration was 3.0 per 1,000 inhabitants (OCDE 2004 cited in Boswell, 2005*) and the OCDE described the main source country-receiving country patterns as: “Moroccans in Belgium; Iraqis and Afghanis in Denmark; Russians in Finland; Moroccans and Algerians in France; Poles and Turks in Germany; Romanians and Ukrainians in Hungary; Albanians, Romanians and Moroccans in Italy; Angolans and Cape Verde nationals in Portugal; Iraqis in Sweden; and Indians in the UK” (Boswell, 2005, p. 3).

The European Union has been responsible for trying to unify the member states’ immigration policies, by elaborating policies to regulate the movements of legal migrants and also of refugees. While, on the one hand, European citizens are increasingly free to circulate, to live and work in other European Union member countries, on the other hand national policies are becoming increasingly restrictive regarding non-European Union migrants. “Fortress Europe” is the term that reflects the European policy of keeping non-European Union residents outside its frontiers (Bolesta, 2004).

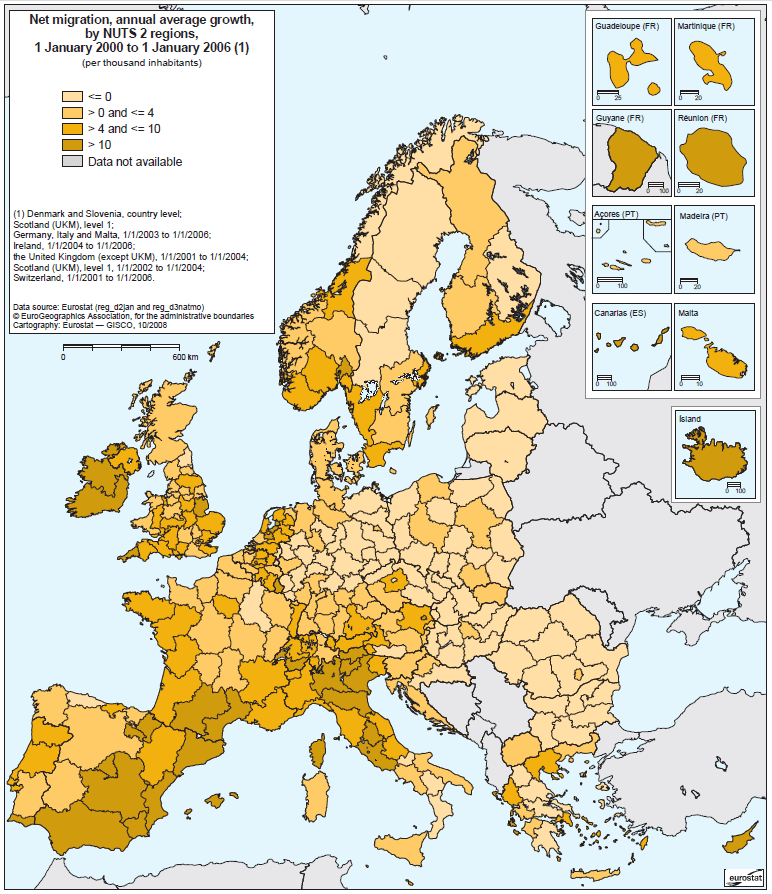

Statistics from 2007 (Eurostat, 2007*, ch. 1) reveal that the population of the EU-25 grew from 376 million people in 1960 to 460 million people in 2005, migration being one of the main reasons for this increment. Net annual in-migration to the EU-25 increased from 590,000 persons per year in 1994 to 1.85 million by 2004. Figure 2* shows the net migration, annual average growth, by NUTS 2 regions, 1 January 2000 to 1 January 2006 in statistical maps from 2008 by Eurostat (GISCO, 2009*). There are clear patterns here of the source and receiving regions from within Europe, although there are also movements into and out of Europe too. These data are clearly out of date now but there is nothing better at present, illustrating one of the problems in understanding migration effects – poor statistics.