6 Predicted migration and resulting population changes

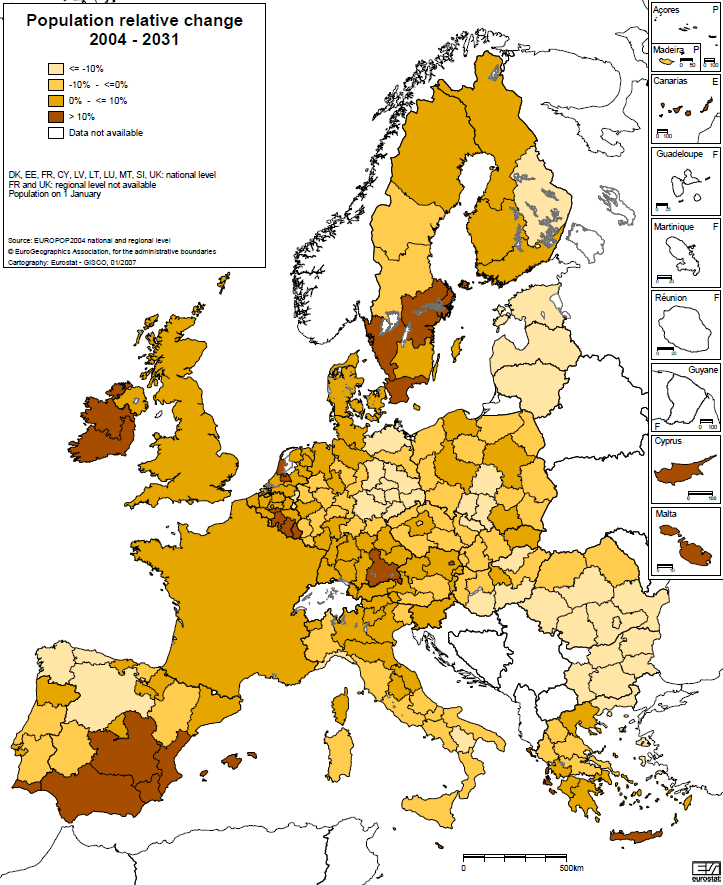

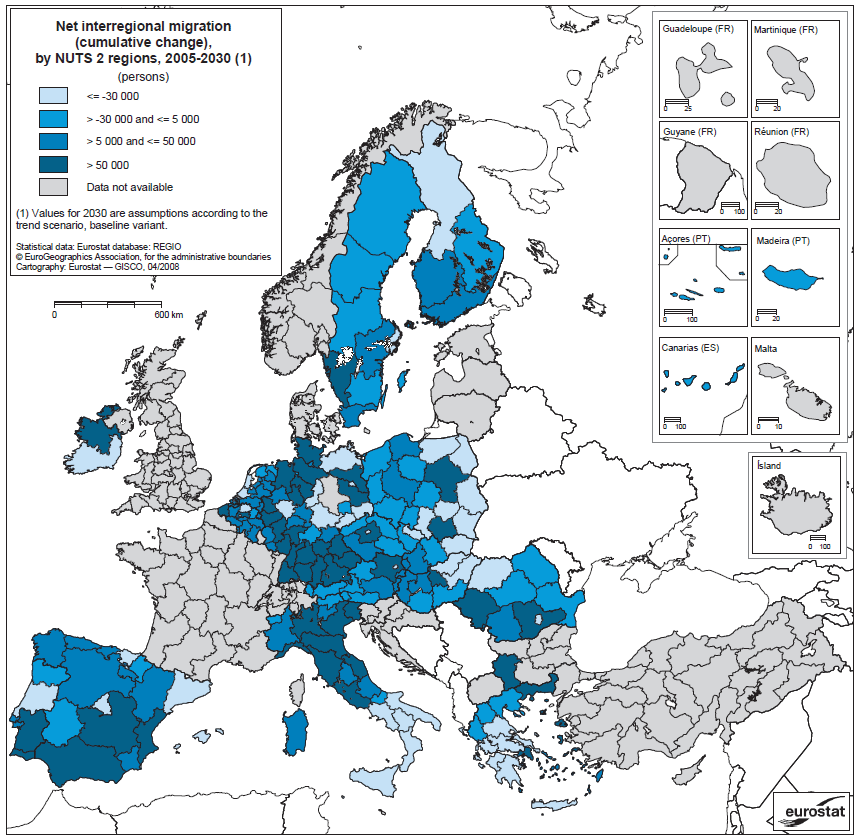

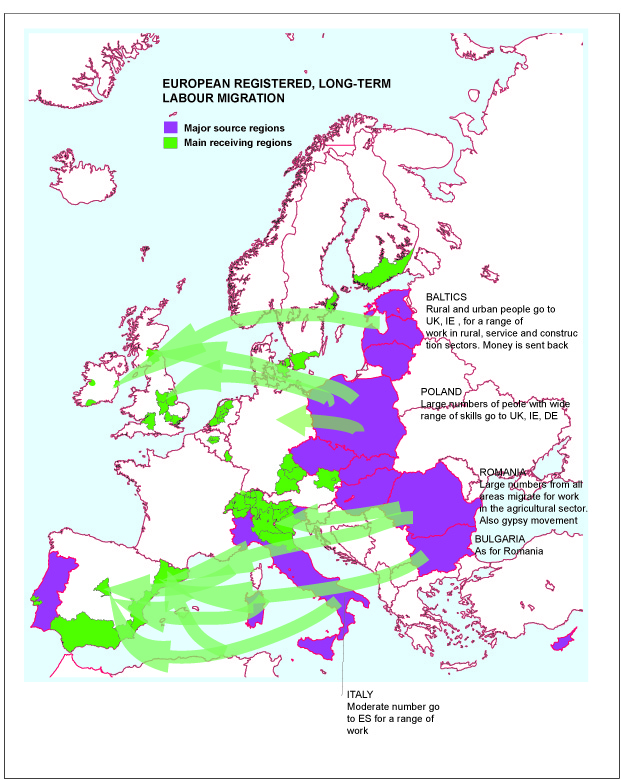

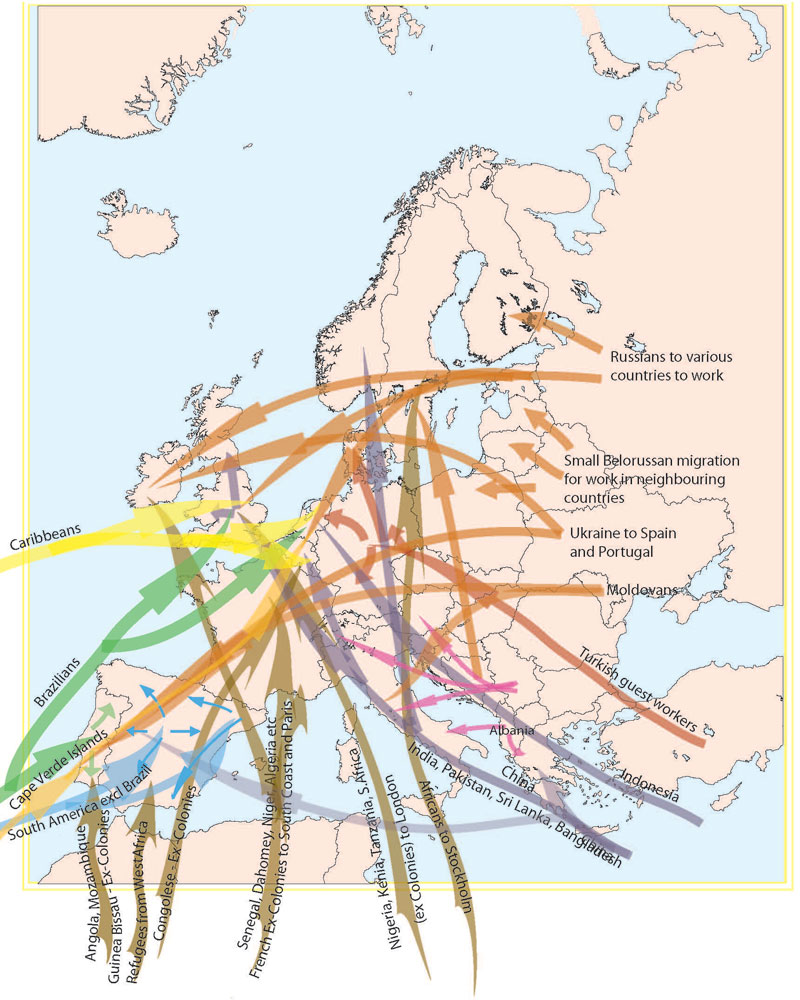

The future migration map of Europe will depend on several factors including the changing balances between push and pull factors which may increase or decrease migration from different areas or in different directions and immigration controls to migration from outside the EU. The overall population of many European countries is expected to increase largely as a result of migration rather than through demographic growth (Eurostat, 2007, ch. 1). The pattern of migration is also affected by the composition of the migrants. Eurostat has produced some forecasts of net population increase and anticipated migration for the years 2004 – 2031. These help to evaluate the effects and to link these to land use change. However, there are drawbacks to these projections, not least because there is incomplete data at a European level and the resolution of the data varies considerably.Figure 3* shows population relative change 2004 – 2031 at NUTS 2 (in general, although for France and the UK it is NUTS 1) while Figure 4* shows net international migration (cumulative change), by NUTS 2 regions, 2005 – 2030 but not for all countries due to a lack of data. This absence of data is a major problem, especially as the UK and France are major locations for migrants to move to while the Balkans and Baltic states are major sources of migrants. In addition these maps and the data underlying them do not capture or present the nature of the migration patterns in terms of flow. Thus the quality of these prognoses for planning or policy responses is questionable. The authors of this paper have tried to improve the understanding of flows by examining the literature sources reviewed above and from this to determine the anticipated main patterns of migration. The pattern for within Europe is shown in Figures 5* and 6* in terms of the main sources and receiving destinations and also the directions of flows between them (Figure 5* shows the primary flows and Figure 6* the secondary flows). The main flows from outside the EU are shown in Figure 7*.

One of the characteristic features of the migration flows from outside the EU is the popularity of the countries which were the former colonial powers in the 18th to 20th centuries as potential receiving countries. This places particular pressures on the UK, France, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal. The other feature is the continuing link between Germany and Turkey and the expected flows from the former Soviet Union, some of which are already fairly strong, such as that of Ukraine to Portugal.

These anticipated flows will present major challenges for many countries in assimilating migrants into society, with potential dangers of the development of more ghettos and urban areas dominated by certain ethnic groups probably living in rather deprived conditions and needing more and more social support, special education programmes owing to language problems and so on. The political implications should not be underestimated either. Social cohesion, national identity and perceptions about over-population are issues that are already being raised by politicians in many countries. In countries where fertility rates have been falling the more fertile migrant populations may affect the balance of ethnic composition in school classes in certain inner city locations, for example and there may also be perceptions that there is some kind of threat to the ethnic make-up of cities or countries which is also on the political agenda in some places.

At this point, we can return to the concept of ‘environmental supportiveness’ to make the point that a balance or fit in terms of the migration-landscape change relationship demands the analysis of multiple issues – those addressing migrants’ motivations and reasons for migration, socio-cultural characteristics, political and economic factors making up the migration process, environmental and ecological impacts as well as legal procedures for each country.