2 Legal framework

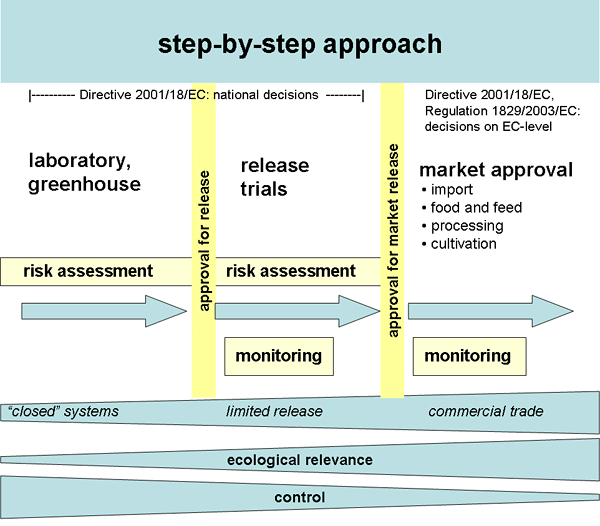

In accordance with the precautionary principle, the Directive 2001/18/EC (European Commission, 2001*) regulates the releases, imports and cultivation of GM crops, applying a stepwise and systematic case-by-case assessment of the risks to human health and to the environment. Annex III B of the Directive 2001/18/EC specifies that the ERA shall encompass an evaluation of a) biological features of the parental plants such as reproduction, dissemination, survivability and geographical distribution, b) details of their genetic modification, c) harmful effects on human or animal health arising from the GM food/feed, d) interactions of the GM plant with the biotic and abiotic environment, and e) impacts of the specific cultivation, management and harvesting techniques. Important elements of this ERA are ecotoxicological tests at the research and development stage, investigating adverse effects of a GM plant in ecosystems that could be affected (Preamble 25 of Directive 2001/18/EC). It has to be demonstrated at each level that the risk for the environment is zero or negligible. In terms of duration and scales of release (Figure 1*) the Directive distinguishes between a) experiments in the contained use system, b) deliberate release for experimental purposes, and c) release onto the market including cultivation.Preamble 24 of the Directive 2001/18/EC recommends that “the introduction of GMOs into the environment should be carried out according to the ‘step by step’ principle.” This means that the containment of GMOs is reduced and the scale of release increased gradually, step by step, but only if evaluation of the earlier steps in terms of protection of human health and the environment indicates that the next step can be taken. Risk-related research should thus be carried out initially in laboratories and greenhouses and then be followed by release-related research and monitoring. In premarket field trials, field plots are limited in time, number and space.

In regulatory practice the step-by-step principle is often not followed. Especially the field testing of GMO in those ecosystems that could be affected in the case of commercial release is incomplete and, if done, the parameters assessed are mostly of agricultural and rarely of environmental value (Dolezel et al., 2009).

For market-approved GMOs the Directive distinguishes (a) a case-specific monitoring (CSM) which focuses on direct and indirect, immediate and delayed potential effects on human health and the environment, identified in the preceding ERA process, and which is limited to a specified time period in which to obtain results and (b) a general surveillance (GS) that aims to identify and record indirect, delayed and/or cumulative adverse effects that have NOT been anticipated in a preceding ERA. In science, regulatory and monitoring practice, full non-anticipation for GS is not feasible. This is because, for any GS activity, there automatically is an effect hypothesis. In contrast to CSM, general surveillance should aim at identifying unforeseen and long-term effects and therefore be conducted over a longer time period and possibly wider area. The general definitions of CSM and GS leave some room for interpretation because cumulative effects, for example, may be either anticipated (then inducing CSM) or unforeseen (leading to GS). There are gradual differences in predictability among the effects. For instance, local effects on cropland can be more easily assessed than effects beyond cropland and on larger scales.

The monitoring results of marketed GMOs contribute to decisions regarding approval or additional precautions, and can enhance the certitude of prognosis for a future ERA. GM crop monitoring is intended to serve as an early warning system to react in case of reported adverse effects and then help in the decision-making process about countermeasures.

Once environmental changes are identified, it is essential to determine whether they are harmful or not. Adverse changes cannot always be attributed to a GMP because there are numerous influencing environmental and agricultural practice covariables (Graef, 2009*; Hails, 2002; Stein and Ettema, 2003*). If harmful, more in-depth studies are envisaged in order to detect causal relationships. In case of a relationship between a GMP and an adverse effect, measures to avoid or minimise effects must be taken. At the same time a new ERA is required. The subsequent results are the basis for decisions on extending GMP approvals, withdrawal of approval, modified risk management, and adaptations of the monitoring plan.

In the case of GMHR crops, there is an overlapping of competencies between the pesticide Directive 91/414/EEC (European Commission, 1991) and the Directive 2001/18/EC on the deliberate release of GMOs. Direct herbicide effects such as for glyphosate are regulated by Directive 91/414/EEC, but adverse effects due to a GMHR plant are not covered by the pesticide Directive. The European Commission therefore recommended that ERA and monitoring of herbicide effects of GMHR crop cultivation, as compared to conventional varieties, be done in the framework of Directive 2001/18/EC (DOC NR ENV/03/23). Some of the adverse effects discussed in the following will thus also fall into the remit of the pesticide Directive.

As outlined by Bartsch et al. (2009), the Directive 2004/35/EC on environmental liability specifically includes the handling and cultivation of GMO that potentially may cause environmental damage such as to protected species and natural habitats under Directive 92/43/EC (Natura 2000 habitats). Any damage that has significant adverse effects on reaching or maintaining the favourable conservation status of these legally defined protection goals must therefore be avoided. Some EU states and/or regions are therefore imposing cultivation bans for Bt-Maize and GM crop release restrictions for field tests within up to 1 km distance from Natura 2000 sites. BfN (2010) is hosting a mapping service in Germany to conform to these distance regulations.