3 Definitions and theories

3.1 The semi-urban condition

Tacoli (1998a*) gives a number of examples – ranging from Senegal to the Philippines over China to Europe – showing different definitions of “city”, “countryside”, and of areas that either are situated geographically “in between” city and countryside, or differ from rural and urban landscapes in configuration, functions, and other characteristics, so that they cannot be called city, nor countryside.

A large number of papers on urbanization and related topics starts from the viewpoint of the ‘nearby city’ as driving factor – hence most studies refer to urban geographic theories and typologies (Antrop, 2000b; Antrop and Van Eetvelde, 2000*; Lewis and Brabec, 2005*). In many cases, the semi-urban areas studied are in the vicinity and under influence of urban cores and thus referred to as “peri-urban” (Allen, 2003*; Cavailhès et al., 2004*; Tacoli, 1998a*; Adell, 1999*; Casaux et al., 2007*).

In the literature, different categories explicating the “semi-urban” condition can be found, which can be divided into two groups. Firstly, there are descriptive categories, which primarily try to develop analytical frameworks under one of the following captions: the urban-rural divide, the fringe, sprawl, and semi-urban landscapes. The second group corresponds to development or strategic categories for sustainable development including garden cities, new urbanism, landscape urbanism, urban agriculture, neo-rurality, and ecopolis.

Only in rare cases, the phenomena are approached from a more explicit rural reference. Gonzalez-Abraham et al. (2007*) write of “rural sprawl” (i.e. urban fabric ‘sprawling’ in a rural land use matrix) and Friedberger (2000) mentions the “rural fringe” being under pressure of urban expansion. When describing the metropolitan area of Phoenix, Arizona, Gober and Burns (2002*) define an “outer rural zone” – thus incorporating this still mainly agricultural region inside a bigger, predominantly urban, context.

The inherent complexity of the semi-urban areas puts the traditional duality of rural vs. urban areas in question (Gulinck, 2004*). To give it some analytical order, Gulinck suggests distinctions between sealed vs. unsealed, open vs. closed, urban and industrial functions vs. rural and natural. This problem is confirmed by Tacoli (1998b*), who states that the high rates of failures of development strategies are often due to lack of recognition of the complexity of rural–urban interactions which involve spatial as well as sectoral dimensions.

3.2 The “divide approach”

The categorical divide between rural and urban is a practical response to clarity in land use policy and tenure. It is deeply embedded in culture, in science, and in planning. Strictly spoken, this divide concept is a denial of a semi-urban or semi-rural state, but it does reflect certain realities. First of all, it implies the possibility for a clear categorization of “urban” vs. “rural”.

Local and regional government agencies tend to apply either an urban or a rural focus (Allen and Dávila, 2002*) on their own definition of their districts. The categorization of districts as rural or urban is often set by thresholds of demographic density. Also, a combination of criteria may be used, including next to demographical numbers the share of agriculture, distance to urban centers, concentration of commercial and administrative activities, and others (Robinson, 1990).

Rural districts, on the other hand, are in most cases defined in an indirect way, as districts in which urban characteristics are absent or scarce (The Wye Group Handbook, 2007). In cases where more direct definitions are pronounced, they generally refer to traditional land use, rural communities and agriculture. Such pragmatic categorization may hide differences in perception within a single area: perceptions of rural and of urban character can vary between native rural people, new residents, tourists, and planners (Tilt et al., 2007*).

The use of criteria and thresholds to define “urban” and “rural” creates apparent clarity, but is at odds with the lack of a fundamental definition of what is precisely urban and what is rural (Countryside Agency Research Programme, 2002*; Theobald, 2001*). Since there are no unique indicators, nor quantitative thresholds with which to distinguish rural from urban areas, it is even more problematic to find sharp guidelines to demarcate semi-urban from urban respectively rural areas.

The urban–rural divide has become a misleading metaphor that oversimplifies and even distorts the realities (Leinfelder, 2007*; Tacoli, 2003*).

3.3 The “dynamic edge”: the urban fringe

The word ‘urban fringe’ suggests a topological category, not a sharp divide or edge, but a border zone of an urban area. In further descriptions its dynamic nature – in terms of pressure from the urban area – is revealed as well. According to Hite (1998*), the fringe is a frontier in space where the economic returns to land from new urban land uses are roughly equal to the returns from traditional land use. In this sense, the fringe is the losing edge of rurality, and steadily moving outward into the countryside.

The countryside at the farther end of this front can be called peri-urban. The urban fringe is characterized by relatively strong pressures for growth compared to more distant rural areas. Space, land use, social composition, and the economic bases of the different communities are strongly differentiated (Bryant, 1995*). According to Hite (1998*), the fringe is the ever continuing expression of global to local impacts on prices and of the relative costs of conflicting land uses and commodities. The potential for urban–rural win-win deals is bleak, unless vigorous counteraction in land use policy in implemented. Declining transport costs and communication costs in the general process of globalization are causing factors. Farmland is an important provider of open space which introduces an important pressure on farmers living in or in the vicinity of the fringe (Ryan and Hansel Walker, 2004*). The U.S. Census Bureau defines urban(ized) areas as comprising of one or more urban cores (central places) and the adjacent densely settled surrounding territory, which is then called the fringe (Kline, 2000*).

Urban fringes as a dynamic “border” zone have been studied often as part of a landscape or phenomenon. Seldom is the fringe itself, as a stand-alone geographical entity object of landscape study.

Examples of these studies are the morphological study of the fringe of Phoenix, Arizona by Gober and Burns (2002), or the study of the fringe areas of Chicago by McMillen (1989*). Indirectly, the landscape ecological properties of fringe areas are also studied when using approaches with urban-rural gradients as methods. An often cited example here is the Phoenix urban landscape study of Luck and Wu (2002*), which covers the entire metropolitan area of Phoenix, Arizona, using a gradient analysis approach, calculating specific landscape metrics to characterize and classify the area.

Next to the morphological properties of the fringe, more attention is given to the study of land use dynamics in fringes, as conversion from agricultural or natural land into urban land (Hite, 1998; Theobald, 2001*), for example in Ohio (Carrión-Flores and Irwin, 2004*), in Canada (Beauchesne and Bryant, 1999*; Bryant, 1995*) or Japan (Mori, 1998*) or in the same sense, the multifunctionality of land use in the urban fringe, as for example described by Gallent et al. (2004*) and Adell (1999*), or by Cavailhès et al. (2004*), who are calling the fringe “the belt outside the city limits occupied by both households and farmers”.

In sociology and economics, the urban fringe can also be considered a well-studied area. Since real estate prices and urban expansion go hand in hand, numerous studies of the urban fringe deal with economic aspects. Well-known examples are Deal and Schunk (2004) who modeled effects of urbanization on land prices, or Libby and Sharp (2003) who introduce the concept of social capital as a socio-economic instrument in urban fringe regions. An example of econometric modeling in fringe areas, where the competition between residential and agricultural land use is explained using variables like distance to the nearest town or metropolitan area (Chicago in this case) can be found in the work by McMillen (1989).

3.4 The dynamics approach: urban sprawl

Sprawl is a term often used to describe perceived inefficiencies of development, including disproportionate growth of urban areas and excessive leapfrog development (Carrión-Flores and Irwin, 2004; Irwin and Bockstael, 2004*). The European Environment Agency sees sprawl as the leading edge of urban growth (EEA, 2006*). In general, most authors and researchers define sprawl as that kind of urban expansion where the rate of land consumption is higher than the increase in population density (Fulton et al., 2001*; Wolman et al., 2005*). Sprawl is an exurban land use change with a footprint exceeding the minimum required for the activity developed (Allen, 2006).

Kasanko and colleagues performed a study on 15 European cities and concluded that whereas cities in the south of Europe tend to become denser, most cities in northern and western Europe become more dispersed in the countryside: so the “fringe” phenomenon makes place for “sprawl” (Kasanko et al., 2006). Whereas a fringe still denotes a specific place, close to some core area, this is less the case for sprawl, which is rather a dynamic process than a geographical area. Sprawl not necessarily radiates from a center, but is a phenomenon that is less dependent on distance constraints. However, the European Environmental Agency still defines sprawl as a “physical pattern of low-density expansion of urban areas, under market conditions, mainly into the surrounding agricultural areas” (EEA, 2006*). According to the same source, this results in a patchy, scattered, strung out, discontinuous and leapfrogged landscape.

Sprawl is not a random phenomenon: much urban development is closely related to infrastructure networks (Ewing et al., 2000*; Schrijnen, 2000*), whilst Felsenstein (2002*) investigated the relationship of sprawl with high-tech agglomerations around bigger cities. McDonnell and Pickett (1990*) define sprawl as an increase in human habitation, with increased per capita energy consumption and an extensive modification of the landscape creating a system that does not depend principally on local resources to persist. Urban and suburban sprawl is one of many inter-linked components of the movement of people across the landscape (Dwyer and Childs, 2004*). Sprawl stays an elusive term: according to Fulton et al. (2001*), it could mean auto-oriented suburban development, or low density residential subdivisions on the metropolitan fringe, or even any kind of suburban growth style, whether driven by population increase or not. The latter definition is regularly used in popular press.

It is difficult to apply one single definition to a problem. Fulton et al. (2001*) state that there is no unique ‘sprawl’ problem in the United States. Sprawl is often confused with ‘general suburbanization’ (Torrens and Alberti, 2000*), without clear empirical foundation. Lewis and Brabec (2005) define sprawling urbanization as a fifth landform next to the four urban types defined by Lynch and Bacon: nuclear, linear, stellar and constellation (Lynch, 1954*; Bacon, 1974). Galster et al. (2001*) define sprawl as a pattern of land use in an urban area that exhibits a combination of eight distinct dimensions of land use in low levels: density, continuity, concentration, clustering, centrality, nuclearity, mixed use and proximity.

An indication of the difficult quest for identity of diffuse expansion of urban development is the large vocabulary in different languages: next to words like sprawl itself, network city, periphery, fragmented urbanization, in Italian città diffusa and città frattale (the fractal city) (Batty and Longley, 1997) are used, in Dutch we find nevelstad (“nevel” meaning mist or haze), rasterstad (grid city), and tapijtmetropool (“tapijt” is carpet) (Urban Policy Project, 2003; Leinfelder, 2007), in French hyperville (megapolis in English) (Bourne, 1996*) and ville émergente (Dubois-Taine and Chalas, 1997).

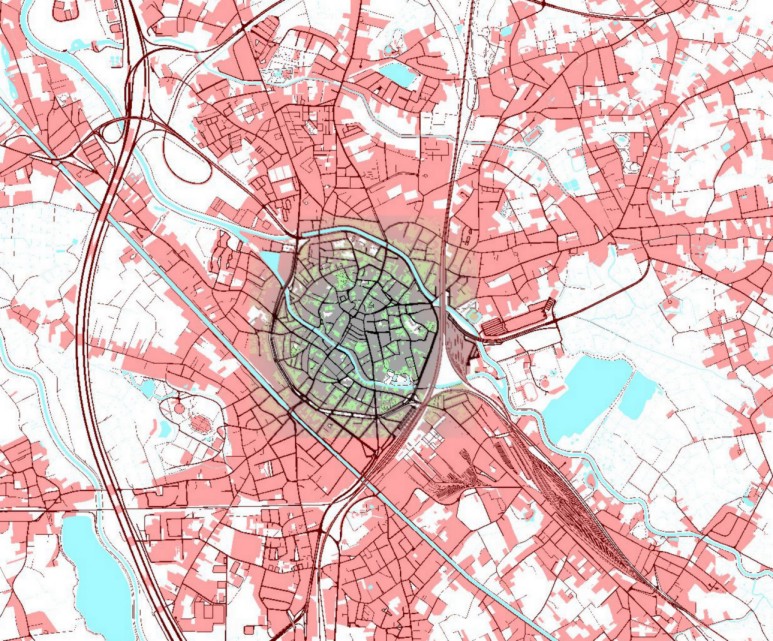

In the older literature about the expansion of urban cores, three main theories can be found: the concentric zone theory first developed by Burgess (1925), followed by the sector model theory of Hoyt (1939), concluding with the multiple nuclei theory first discussed by Harris and Ullman (1945). Some of the more recent city model theories include the catastrophe theory or the chaos theory of Wilson (1976, 1981), the dissipative structure model, the theory of self-organization or fractal models (Batty and Longley, 1987). Most of these concepts imply the reference of the classical, concentrated urban condition and describe some form of new urban conditions at low spatial density. In metropolitan areas or where larger cities are located close to each other as is the case in many regions in Europe (Hagoort et al., 2002*), in the Bay Area in California (Schrijnen, 2000*), in the Boston-Washington megapolis or in Japan (Mori, 1998*), the cities and their surrounding peri- or semi-urban areas merge into large city regions, where residential areas, retail, services, industries, leisure centers and parks form a network of functional nodes connected by transport infrastructure: urban landscapes often referred to as conurbation (Countryside Agency Research Programme, 2002*; EEA, 2006*), superburbs (Bourne, 1996*), grid cities (Schrijnen, 2000*) or constellation regions (Lynch, 1954).

3.5 Toward a more holistic approach: the semi- and peri-urban landscape

Many authors claim two important consequences of sprawl, the urbanizing landscapes and fringe land use dynamics: first, landscape dynamics like sprawl cause such changes that the resulting land use is hard to be classified as either rural or urban land use. Land use becomes blurred (Dwyer and Childs, 2004). Secondly, because of the dynamic character of the fringe areas, they become so scattered, broad or detached from the city core, that defining them as the border or fringe between city and countryside becomes ambiguous (Tacoli, 1998a*) or with a “fuzzy boundary” (Yang and Hillier, 2007).

Cavailhès et al. (2004) recognizes a sprawled area beyond the city limits and suburbs , but no more real countryside: a belt outside the city limits occupied by both households and farmers. As a result of sprawl, a contiguous territory with specific characteristics develops (Kline, 2000) . This is the rationale to lift both “fringe” and “sprawl” toward the level of “landscape”. Instead of looking at some badly analyzable spatial and functional chaos, some organizational and functional logic is searched for. Few authors, however, will explicitly mention the rural–urban transition zone as a specific landscape. Moreover, landscapes strongly affected by urbanization do not fit the traditional schemes of landscape definition and analysis, which are strongly rooted in historical reference frameworks (traditional rural landscapes, natural landscapes) or in theories and practice of landscape design.

In a first group of articles, semi-urban landscapes are seen through a strong urban bias. Allen and Dávila (2002*) define a peri-urban interface: a mosaic of agricultural and urban ecosystems, subject to rapid change with a large social mix and with clearly measurable distinctive features (Allen, 2003*). Another definition of the area ‘between’ countryside and city is what Irwin and Bockstael (2004*) call the exurban areas beyond suburbia on the rural–urban divide. Bourne (1996*) describes an evolution towards “exurbia”, a semi-urban landscape beyond suburbia: suburbs become edge cities and they become “superburbs”, a phenomenon frequently studied in the United States (Bourne, 1996*; Bugliarello, 2004a; Felsenstein, 2002*; Holden and Turner, 1997*; Theobald, 2001*). Bourne also states that there is no clear border between suburbia and this exurbia that contains edge cities and semi-agricultural, semi-urban landscapes. Yang and Lay (2004*) see these landscapes under urbanization pressures as “nurtured landscapes”, literally fed by the cities which they enclose as peri-urban area. In densely populated areas with extensive networks of cities and town, the semi-urban landscape itself is enclosed by the city fabric, and thus “nurtured” by multiple sources. Wolman et al. (2005*) propose the concept of the extended urban areas, based on housing density and commuting patterns.

In contrast with the former paragraphs, some authors partly reject the dependency-from-cities vision. According to Adell (1999*), peri-urban zones are dynamic, both spatially and structurally, and form distinctive areas of agricultural and non-agricultural activity. Alfsen-Norodom defines the entire area around metropolitan areas as a separate “biosphere” – a concept to see a landscape with dense and less dense built-up areas and generally a hybrid land use as a entirely “new form of (dynamic) landscape”, with its own biotopes, ecosystems and landscape dynamics (Alfsen-Norodom, 2004*; Alfsen-Norodom et al., 2004*). A typical “biosphere” related variable, carrying capacity can be useful as variable, to measure the semi-urban area, which can be seen as a heterogeneous mosaic of natural, production and agricultural ecosystems (Allen, 2003*). Also Antrop and Van Eetvelde (2000*) define the urban fringe as a landscape and not just a transition between an urban and a rural landscape. These ‘new’ landscapes are created by a functional heterogeneity and are much more complex in reality than many city or landscape models may show. Typical city models are not sufficient (Antrop, 2004*).

Some theoretical support to develop a diagnostic framework for semi-urban landscapes can be sought in the analysis of its functional system. In urban fringes, a number of fluxes meet (Tacoli, 1998a, 2003*): urban ‘entities’ (people, systems, industry, waste, products, culture, …) enter these areas and are substituted for agricultural systems, products, even people. In a way, these semi-urban areas function as a transfer area between urban and rural systems. Because of this, they are hybrid landscapes with both rural and urban properties, but also attract their own, specific kind of ‘semi-urban’ entities, such as ‘urban agriculture’ (Beauchesne and Bryant, 1999*). This can be considered a rather optimistic viewpoint, stressing added value to and specific properties of the urban-rural mix.

3.6 Semi-urban areas in fast developing countries: Desakota

The Desakota concept deserves to be mentioned here: where traditional theories relate the rapid growth of cities in third world countries to fast depopulation of the countryside, in Southeast Asian regions another process is defined: the rural population, living within the hinterlands of large (rapidly industrializing) cities, is spontaneously transforming their rural lifestyles into urban ones without leaving their rural environments. So, in this approach, cities are not really expanding but the neighboring countryside is transforming ‘itself’ into a specific kind of semi-urban fabric (Adell, 1999; Heikkila et al., 2003; McGee, 1991; Xie et al., 2005; Yokohari et al., 2000*).

3.7 Development models for fringe, sprawl, and semi-urban areas

From the early 19th century industrial towns, urban planning became the official and most adequate tool for the organization of urban fabric in and around towns and cities. The younger the urban planning theories, the more attention they pay to concepts such as sustainable development, landscape conservation, and urban ecology. In the following paragraphs, a brief overview of development theories is given. Some of these concepts or theories are specifically developed for the urban planning in semi-urban areas or are developed as an answer to fringe problems and sprawl. Other theories are more general urban planning theories, which however can be applied to those areas that are the subject of this paper. The main difference between these ‘specific’ theories and the ‘general’ theories is the basis where they were generated from: the specific theories are often developed as an answer to a specific problem (e.g. sprawl), while general theories involve a whole list of goals.

Rural planning principles were not often found in the literature, when using the review method as described earlier. Tilt et al. (2007) did study the perception of the rural character in areas subjected to sprawl and compared them with the perception of “pure” rural areas. Tress and Tress (2003) state that when planning urban expansion or other forms of urban driven development in the countryside, all stakeholders or people affected by this should be included in developing the plans. Like Tilt and co-workers, they also use visual materials in this transdisciplinary approach. Allen and Dávila promote the idea that semi-urban planning and urban planning should be the same discipline, especially in urban fringe areas (Allen, 2003; Allen and Dávila, 2002).

Maybe the oldest answer for sustainable semi-urban and peri-urban areas was the Garden City Movement, founded by Howard in 1898 (Lee and Ahn, 2003*). The central idea is to create a cluster of communities or suburbs, all surrounded by greenbelts and planned with a balanced area for industry, agriculture, services. Hundred years later, the Garden City Movement also formed a base for the urban design movement New Urbanism. An interesting comparison between both movements can be found in the study of two cities, Kentlands and Radburn, by Lee and Ahn (2003). Yokohari et al. (2000*) and colleagues applied the greenbelt idea from the Garden City concept on Asian mega-cities.

New Urbanism is a (architectural) design movement that specifically focuses on the improvement of the initial chaotic, inefficient and ‘ugly’ layout design of the suburban and exurban landscapes (Bourne, 1996; Katz, 1993). It is a movement ‘against’ sprawl, with a main goal being the preservation of open space (Talen, 2005; Congress for the New Urbanism, 1996): bringing order and coherence to the growing ‘Edge Cities’ on the urban fringe, by introducing (walkable) multifunctional and integrated urban areas on different scales (from town to neighborhood), always with a strongly integrated open space system (Walmsley, 2006*). New Urbanism as a tool against sprawl is illustrated in a study by Skaburskis (2006) in Toronto, Canada.

Partly parallel to the New Urbanism approach, partly as a continuation and refinement of these theories, Landscape Urbanism is a modern design theory that proposes an alternative to sprawl inducing planning processes. Landscape Urbanism places the landscape (on or in which urbanization occurs) central as a model for urbanism and as a model for process as opposed to common planning, design, and architectural theories and policies (Allen, 2001; Hackworth, 2005; Shannon, 2004; Waldheim, 2006).

Urban ecology is an interdisciplinary science, where any urban system with its main components – human activity and artificial land cover, in conflict or competition with natural land cover – is studied as a ‘natural system’ with its own specific ecology (Breuste et al., 1998*; Collins et al., 2000). These theories go back to the basic Ecopolis concept of Tjallingii (Pearce, 2006; Tjallingii, 1995), or the Ecocity builders (Register, 2002; Rees, 1999). It is a model for sustainable city planning, including urban agriculture, which measures avoiding sprawl or mitigating sprawl effects, avoidance of urban heat islands, and other ideas.

New forms of agriculture adapted to urban and semi-urban conditions are getting more and more attention (Jarosz, 2008). Urban and peri-urban agriculture, as (geographically) opposed to large-scale, intense, and traditional “rural” agriculture, is an example of modern agriculture (Tacoli, 1998b, 2003). It is a reply to a growing demand for short food chains, organic farming and high quality agricultural goods supply. Because of phenomena like sprawl, agricultural land in the vicinity of the urban fringes or in semi-urban areas is highly fragmented with, relative to traditional farms, small plot sizes and a small production in absolute figures. These farms, however, form an ideal multifunctional land use, not only for food production (be it smaller and less economically efficient in some cases), but for production of specific regional products, organic farming, agri- and eco-tourism (Beauchesne and Bryant, 1999; Bryant, 1995; Countryside Agency Research Programme, 2002*).

The core of the concept of neo-rurality is to consider values, services, and functions linked to the unsealed soil beyond being a mere component of an urban or rural environment, and which are being managed and sustained by specific compartments of society. Distance to urban components is not a criterion. The concept is useful but not exclusive to semi-urban areas (Gulinck, 2004*). Land-bound urban agriculture is an example of a neo-rural function, as is the acknowledgement of unsealed soil for water retention or microclimate regulation.

Smart growth is a recent planning concept now becoming popular in the United States as a framework to dam sprawl and work on sustainable city development. Although it is based on urbanistic principles and so primarily focused on the human-dominated environment, it incorporates elements from various other planning frameworks for sustainable (urban) development such as anti-sprawl measures, greenbelts, rural development near urban fringes and multifunctional land use (Burchell et al., 2000; Daniels and Lapping, 2005*; Danielsen et al., 1999; Duany and Talen, 2002; Irwin and Bockstael, 2004; Walmsley, 2006).