3 Analytical frameworks

While the previous section focussed on the definitions of multifunctional agriculture and described the different ways to approach it, this section provides analytical frameworks to assess the multifunctional character of farm systems. Important emphasis will be laid on the link between commodity and non-commodity production.Although the supply and demand side visions on multifunctionality, described in the previous section, place another emphasis on the concept, it is rather clear that the core elements of multifunctionality are: (i) the existence of multiple commodity and non-commodity outputs that are jointly produced by agriculture; and (ii) the fact that some of the non-commodity outputs exhibit the characteristics of externalities or public goods, with the result that markets for these goods do not exist or function poorly.

In order to connect both approaches two aspects become important:

- The coupling between commodity and non-commodity output in agriculture: in general, literature reveals that jointness between these outputs is weak as long as externalities are positive (and conversely). This result is supported by an empirical study referring to OECD countries (Abler, 2001*).

- The spatial scale of non-commodity output production: the question of spatial scale is important (from farm to landscape level) because diversity in systems (often linked with higher multifunctionality) can be reached by making individual farm systems more diverse or by connection at the territorial level of on itself specialised farm systems.

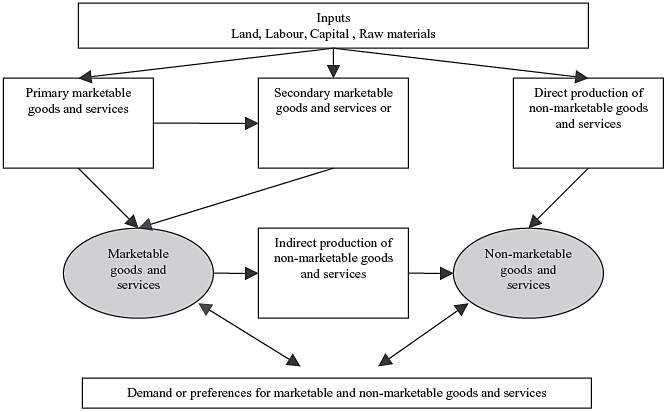

To study whether a farm, sector, or region is characterised by a multifunctional production system different analytical frameworks can be used. Figure 4* is an own attempt to bring together the supply and demand vision using a farm system approach. In this framework it is assumed that the farmer can use its primary inputs (land, labour, capital and raw materials) to produce primary commodities such as food and fibres (traditional products like milk, grains or wood or les traditional products such as bio-energy crops) or less traditional products or services (such as agro-tourism or wind energy). He can also combine (part of) these primary outputs with primary inputs to transform them into secondary marketable outputs such as yoghurt or cheese, or bio-energy (e.g. in case the farmer transforms energy crops or by-products of his primary production into energy). Both the primary and transformed goods and services mentioned are marketable and thus commodities. In addition a farmer can also produce (intentionally or not) directly non-marketable goods and services such as landscape elements, biodiversity or other amenities (in case of fallow land e.g.) or indirectly affect non-commodity values or outputs through the production of both his primary or secondary marketable goods and services. By using the word services we incorporate activities such as farm tourism, landscape care, social care activities, but also non-intended services such as carbon sequestration, cultural services, consequences for environmental quality and so on.

Within a given market and policy setting, the economic activities of the farming system will result in a certain combination of the joint products, or in other words result in a specific configuration of the bundle of outputs. In order to connect this to the demand function we can then analyse whether this output bundle corresponds with societal demand or preferences. It is clear that in present Western societies the preferences for the output combination is different (e.g. a higher preference for environmental values) than e.g. 50 years ago when food supply and security were more important.

The above framework broadens the traditional view on farming and incorporates the vision on rural systems of e.g. van der Ploeg and Roep (2003*) or Belletti et al. (2003), who advocate the broadening of traditional agricultural production through diversification, deepening and regrounding. The conceptual framework can further be used at farm, sector or regional level. At farm level we may look at multifunctionality by analysing the outputs of the economic activities of that farm (either specialised or diversified), while at sector level we can analyze the output bundle of the whole farming sector. At regional level, we will be interested in the output bundle of the territorial system composed of specialized and non-specialized farms and other enterprises.

To know whether the studied system is multifunctional it becomes important to study the technical linkages between non-commodity and commodity outputs (complementarity and substitutions between them), and to define the relationships between the production factors within the agricultural production process which give rise to such linkages (Ferrari, 2004). Maier and Shobayashi (2001), Cahill (2001*) and Vanslembrouck and Van Huylenbroeck (2005*) provide some guidelines to analytically investigate the linkages. They suggest looking at the following issues:

- the extent to which the non-commodity outputs of agriculture are linked to or can be dissociated from commodity production;

- whether there are economies of scope in the joint provision of commodity and non-commodity outputs;

- whether and how the production linkages are influenced by site-and area-specific conditions (spatial dimension);

- the possibilities of alternative provisions of the non-commodity outputs. Even if there is jointness with agricultural production, other providers can exist.

- finally the mutual influence among the non-commodity outputs or with other words the dependencies within the bundle of outputs.

Based on the above framework, Van Huylenbroeck and Vanslembrouck (2001*) give some concrete examples (see Appendix A) of joint non-commodity outputs in agriculture: employment, food security, landscape, biodiversity, environmental quality (soil, air, water), cultural heritage (see Table 3 in the Appendix A).

These examples reveal the following: first of all, the link with the production level is only clear in case of negative externalities. In most other cases the coupling with the production level is weaker (see also Abler, 2001). This has to be interpreted as follows: agriculture or any form of cultivation is in most cases a necessary condition to obtain the non-commodity output, but the yield on itself is not as important. In a few cases however, above a certain level of production the non-commodity output decreases or is endangered (e.g. meadow birds are endangered if the farmer wants a first cutting of his grassland earlier than the breeding season, genetic diversity is not compatible with having only high yielding varieties).

Secondly, in all cases studied, the non-commodity output is dependent on the applied farm practices, systems or technologies. This confirms the production potential model of joint production stating that it will depend on economic conditions at what point of output combination farmers will produce. In most cases the non-commodity output is also linked to agricultural structures: specialisation and increased scale of farming have caused larger physical structures that allow the use of more modern technologies, resulting in less multifunctionality. All these factors together may contribute to the underprovision of certain functions. A specific problem is that the level of jointness is in most cases depending on topography, soil quality, climate conditions and so on and thus spatially differentiated, causing problems of competitiveness in case measures are taken in a particular region.

A third aspect is in how far non-agricultural provision of the non-commodity output is possible or in other words in how far delivery of non-commodity outputs can be de-coupled from commodity production. In theory it is sufficient to conserve the cultivation practices from which the non-commodity output depends on even if the commodities are not sold, meaning that the non-commodity output does not depend on the sales level. In practice however it will in most cases be a very expensive option to decouple the non-commodity production from commercial farming. Conservation of old practices will therefore only be considered either in the case of a high cultural heritage or other social value (e.g. conservation of high fruit trees) or in the case of a high ecological value (e.g. farming practices in an agro-ecological landscape conservation area). For non-commodity outputs with a high dependence on farming and for which the requirement is to reduce the intensity of farming, commercial farming will often be the most economic solution and instruments need to be found to give incentives to farmers to indeed reduce the farming intensity.

Fourthly, Van Huylenbroeck and Vanslembrouck (2001*) focus on the interdependencies among non-commodity outputs. In general, they found a conflict between social functions (employment and rural viability) and environmental functions of agriculture. The reason is that (partial) de-coupling will in general be linked to a reduction of the employment (directly or indirectly because of weakening of the competitiveness), at least if no instruments are found to remunerate the higher costs for the lower production of commodity outputs. In some cases there may be competition among some functions such as e.g. meadow bird conservation and bio-diversity in the meadows as both non-commodity outputs require different farming practices.

Finally, the authors analyse to what degree reductions of commodity prices are creating market failure in the provision of non-commodity outputs. A positive relation exists when as a result of price reductions, more extensive beef production systems are developed, which are good for meadow birds or for field flora. This is however only true as long as farmers do not switch to other commodities (e.g. ploughing their land). In other cases the effect is negative because price reductions stimulate farmers to cut further on costs and to apply more efficient farming systems which are less compatible with the delivery of the non-commodity output.

The examples (confirmed by the analysis of Abler, 2004, based on a larger set of examples) show that the analysis of the coupling between the non-commodity and the commodity outputs has to be done carefully to detect the nature of the jointness in production. An important point (see also Cahill, 2001) is that even if separation of commodity and non-commodity outputs is technically feasible, there may be potential for economies of scale. This means that joint production of several outputs will be cheaper than the separate production of commodities and non-commodities (if already possible because they will compete for the same production factors, in particular land). Further if jointness exists, an examination of the extent to which it is related to the choice of farming system and technology (and to what extent these relationships can be changed) is required (see also Section 2).